John Jay Knox (Washington, DC)

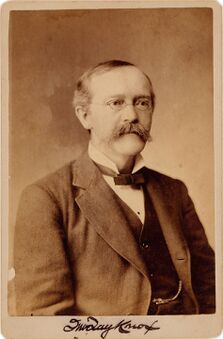

John Jay Knox (March 18, 1828 – February 9, 1892) was a talented nineteenth century banker who rose to become the country's top regulator of national banks. [1]

Biography

Antebellum banking in the Midwest almost always had its roots in the east coast. Jay and Henry Knox, sons of banker John J. Knox of New York, followed in the same career path as their father. They, like many others in the 1850s, saw the wealth of opportunities available in the new territories of the United States, and could not resist the allure of moving westward to build their families and fortune. This is the story of John Jay Knox and his adventure in Minnesota banking before moving to Washington, D.C., where he climbed through the political system to bring his unique experience to the office of Comptroller of the Currency.

John Jay Knox, Jr. – known to his close friends and family members as Jay – was born on March 19, 1828 to John Jay Knox, Sr. and Sarah Ann Curtis in Knoxboro, Oneida County, New York. The senior Knox was a successful merchant and in 1839 organized and became president of the Bank of Vernon, a note-issuing bank organized under the free banking law of New York, not far from their home.

Oneida County sits in the Mohawk Valley between the Catskill Mountains to the south and the Adirondack Mountains to the north, in central upstate New York. The Erie Canal, completed in 1825, was constructed through this natural pathway and made this region a highway for transportation between New England and the Great Lakes. This location undoubtedly afforded the Bank of Vernon to thrive, and the young Knox brothers to learn the banking business directly from their father. Jay would take ready advantage of this resource early in his career.

Jay received his early education at the Augusta Academy and the Watertown Classical Institute. In 1845, he left home to attend Hamilton College just west of Clinton, New York. It was a practical choice. Hamilton was not only the closest college near the family home, but it also was well respected as a place to gain the foundational skills for a professional career.

Upon graduation in 1849, he went to live with his sister Elizabeth and their family in Vernon, and gratefully accepted a position of teller at his father’s bank with a salary of $300 per year. He stayed there for only two years, however. In 1852 he leaned on his father’s experience, packed his bags, and left for Syracuse to help organize the Burnett Bank. This was another note-issuing bank, and Jay may have his first opportunity to sign notes while custodian of this institution. His involvement at Syracuse was to last nearly four years, and in 1855 he moved south near the Pennsylvania border to start up the Susquehanna Valley Bank of Binghamton, New York. He was named cashier and signed its earliest banknotes.

Not long after, Jay was ready to heed the call of adventure. In 1856 he set his sights westward and moved to Saint Paul, a rapidly growing settlement in Minnesota Territory. As Minnesota explicitly forbade the issuance of banknotes, he could not organize the kind of bank with which he was familiar, so had he to adapt. One of his first financial activities was to sponsor the running of the first steamboat on the Red River of the North. He was one of a few financial supporters to pay for the transportation of a steamboat overland from Sauk Rapids to Breckenridge, in the midst of winter. The following year he founded J. Jay Knox & Co., a private banking house created with the financial backing of his father. His brother Henry yielded to Jay’s call to move west and joined him in Saint Paul.

Although forbidden from issuing banknotes, the Knox brothers observed from other private bankers that there was an easy workaround for that constraint, and they, too, joined the party. Bankers in Minnesota Territory routinely obtained quantities of notes from spurious or failed banks at little cost, and used them as their own media by simply writing an endorsement on them. It was a technicality that was frowned upon in the local newspapers, but there was not enough political interest to strengthen the laws. Besides, work was underway to organize Minnesota as a state, and among the proposed statutes was one for legal free banking, with the authority for banks to issue notes. In May 1858, Minnesota became the 32nd state, and the rush was on for local banks to organize under the new law.

A critical failing of Minnesota’s free banking act was that the state auditor was authorized to accept the newly issued Minnesota 7s as security for note issue. These were the Railroad Bonds, used to finance the construction of railroads in the new state. The problem was that these bonds were thinly traded, and accepted by the auditor at a rate well in excess of their market value. Banks obtained them at steep discounts, deposited them with the auditor, and issued banknotes against them for up to 95% of the nominal value of the bonds. Some of these banks were actually organized by the railroad contractors, thereby giving themselves a ready outlet for bonds received from the state for railroad construction.

The Knox brothers did not immediately jump into the legal note-issuing business right away, however. It may have been a matter of not having enough financial or political capital to get going. Being relatively new to the city, they were cautious against partnering with those whom they knew little about.

The cost of entry to Minnesota’s free banking system was to fall dramatically as the market for Minnesota 7s crashed over the next couple years. The natural fallout from this was that some banks did not shore up their security and allowed their banks to fail, leaving note-holders with substantially depreciated banknotes. The worst of these left notes worth only about 16 cents on the dollar.

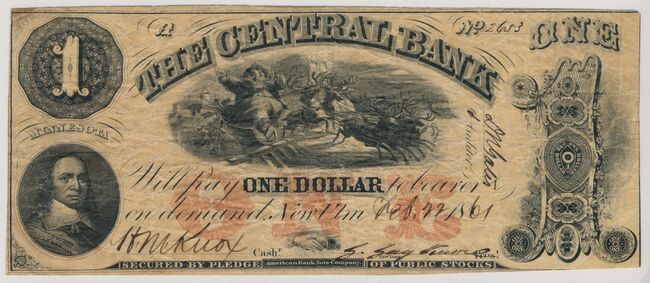

The Central Bank of New Ulm, a German community located about 100 miles southwest of Saint Paul on the Minnesota River, was one of the poorly capitalized free banks. It is apparent that the remote location was deliberately chosen so as to reduce the likelihood that notes would find their way to the home office for redemption. It was organized in May 1859 by John W. Northfield and Franklin Steele, more or less players in the market for junk bonds, but not so much bankers. They hired August H. Wagner, a merchant in New Ulm, to serve as vice president, and Albert H. Merrick, a bookkeeper in Saint Paul, to be the cashier. These men signed some $23,000 in notes of the Central Bank and pressed them into circulation through making loans.

Right away the organizers of the bank were dealt a financial setback, as just a month after the bank received its circulating notes in June from the auditor, the circulation/bond ratio requirement was reduced to 60%. If it was to remain solvent, the Central Bank had the option to deposit more bonds or reduce its circulation. Whereas at this time many bank owners walked away and let their banks fail, Northfield and Steele opted to return $6,800 in notes, leaving the ratio exactly at the minimum requirement. With 27 $1000 bonds on deposit with state auditor, the new valuation fixed the worth of the bank at $16,200 less the value of banknotes outstanding. They just had to maintain an office where they could redeem their notes on demand at par. As the opportunity for arbitrage dwindled, the operation became nothing more than a hassle.

Perhaps with some optimism that the Minnesota 7s were undervalued, the Knox brothers purchased the Central Bank in October 1859 from Northfield and Steele. It was really a bet on the future of Minnesota 7s and the cost of this investment had limited downside, for they, too, could walk away should the investment sour. The outright purchase price was likely not very costly, but they assumed the liability of notes outstanding. They already had an office where they could tend to note redemption, and in many ways this was similar to their previous practice of endorsing notes. The market for Minnesota 7s was stable for the time being; however, the worst of its tortuous fall was still to come.

The banking business was good into 1860 and that spilled into the personal lives of the Knox brothers. Jay and Henry built a new house at 26 Irving Park in Saint Paul, in an exclusive neighborhood for the city’s elite. By this time Henry had married and Jay lived with his sister-in-law Charlotte, his young niece Carrie, and two female servants from Ireland.

It appears that notes of the Central Bank actually did enjoy acceptance and heavy circulation within the Saint Paul community. They probably traded close to par, being that they could be redeemed at any time by walking into the Knox banking house. Indeed, most of those notes that have survived to this day show heavy wear. In December 1860 the Knox brothers returned two groups of notes totaling $1,832 to the auditor’s office, and immediately received a like amount of new bills to replace them. In all likelihood, they were well worn and not fit for continued use. These new notes were eventually signed and released by the Knox’s in late February 1861.

Optimism faded as the battles of the Civil War greatly pressured bonds of the northern states in the early summer of 1861. Even the mainstay bonds used in the security of banknotes issued elsewhere, like Ohio 6s, suffered serious losses and forced the failure of banks nationwide. This, too, was the tipping point for free banking in Minnesota. Any hope that Minnesota 7s would eventually find their footing was extinguished. The Knox brothers recognized this and gave up their campaign of issuing notes and supporting the circulation of the Central Bank. J. Jay Knox & Co. closed its doors in June 1861 under the weight of the financial crisis, forcing the closure of the Central Bank.

As bond values tumbled, Jay accumulated $10,800 worth of his bank’s notes and returned them to the auditor’s office in exchange for 18 Minnesota 7s, and hurried to sell them as quickly as possible. His instincts were correct, as about a year later the bonds traded in New York at just 18 cents on the dollar.

At this point the Knox brothers did walk away, and cut further losses from their failed investment. The state eventually forced the bank into liquidation, and the state auditor sold the $7,000 of bonds remaining on deposit for a deep discount, leaving only enough hard money to pay bill holders 30 cents on the dollar to cover the $4,200 in banknotes that were outstanding. The Knox’s were sued by noteholders suffering alleged losses over the next few years.

Jay’s personal experience in state banking provided ample background for essays he wrote that appeared in the February 1862 and January 1863 editions of the Merchants’ Magazine and Commercial Review, a widely read trade publication, which supported Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase’s vision of a national banking system. He owned and operated his bank under the kind of system that he criticized in his writings in support of national banking – one with weak protections for note holders. Knox later would write about the history of private banking in the United States detailing many state banking experiments, but never again would he or his colleagues ever mention his disastrous experience with the Central Bank.

Despite his failure in state banking, Jay’s article was noticed by the Treasury Secretary, who made him an offer to serve in the Treasury Department as a disbursing clerk. Jay accepted the position in 1863 and moved to Washington. He was more than pleased to leave his problems behind in Minnesota, but Henry opted to stay and later served in the public sector. Jay’s years of service were rewarded by being appointed Comptroller of the Currency, the top official who oversaw the regulation of national banks throughout the country, in 1872. He held this position until 1884, when he returned to the private sector.

Knox was also an ardent student of U.S. paper money and financial history. In the year he retired from public service he published his first book, United States Notes, which was an examination of the history of U.S. issues from colonial times to his day, brought about by the urging of his friends and colleagues. It is especially fitting that his portrait was selected for the new $100 design of series 1902 national bank notes after his death in 1892.

It is interesting to note that Jay wrote his pre-Washington signature as J. Jay Knox. His signature on New Ulm banknotes matches that found on contemporary letters, court documents and records from the Minnesota auditor’s office, so there is no question about the authenticity of his autograph. However, the 1861 signature is stunningly different in appearance compared to later known examples of his autograph found twenty years hence on Comptroller documents. What caused such a radical change? We may never know, but Jay may have taken a page from Francis Spinner’s playbook and developed a new, authoritative signature for his administrative career. After all, Jay was good at adapting to his environment, even in the little things that may have provided him an edge.

Bank Notes Issued

| Signers | Merrick & Wagner | Knox & Knox | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denomination | Serials | Notes | Serials | Notes | Total Issue |

| $1 | 1-2600 | 2,600 | 2601-2832 | 232 | $2,832 |

| $2 | 1-2200 | 2,200 | 2201-2700 | 500 | $5,400 |

| $5 | 1-1800 | 1,800 | 1801-1920 | 120 | $9,600 |

| $10 | 1-700 | 700 | None | 0 | $7,000 |

| Total Notes | 7,300 | 852 | 8,152 | ||

| Total Amount | $23,000 | $1,832 | $24,832 |

Bank Officer Summary

During his banking career, John Jay Knox was involved with the following bank(s):

Bank of Vernon, Vernon, NY

Burnett Bank, Syracuse, NY

Susquhanna Valley Bank, Binghamton, NY

J. Jay Knox & Co., Saint Paul, MN

Central Bank, New Ulm, MN

Exchange National Bank, Norfolk, VA

National Bank of the Republic, New York, NY

Source

- ↑ This article was originally published in Paper Money, the journal of the Society of Paper Money Collectors. See https://www.spmc.org/journals/paper-money-vol-lvii-no-2-whole-no-314-marchapril-2018.

Hewitt, R. Shawn. "John Jay Knox and the Central Bank of New Ulm." Paper Money, No. 314, March/April 2018, p. 125. Chattanooga, TN: Society of Paper Money Collectors (2018).

References

Berndt, Gez. V. J. Ansicht von New Ulm, Minnesota. Cincinnati, O.: Lith. von Ehrgott, Forbriger & Co., [1860]. (imagelink: http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display.php?irn=10443166)

Dana, William B. Merchants’ Magazine and Commercial Review. New York: William B. Dana, 1862-1863.

Evans, George G. Illustrated History of the United States Mint. Philadelphia: George G. Evans, 1885.

Hewitt, R. Shawn. A History & Catalog of Minnesota Obsolete Bank Notes & Scrip. New York: R. M. Smythe & Co., 2006.

Knox, John Jay. A History of Banking in the United States. New York: Bradford Rhodes & Company, 1900.

Knox, John Jay. United States Notes. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1884.

Minnesota, 1860 Federal Census: Population Schedules. Washington: National Archives & Records Administration, 1964.

Minnesota Historical Society. Auditor’s Records. Archives of the Minnesota Historical Society, Saint Paul, Minnesota.

New York, 1850 Federal Census: Population Schedules. Washington: National Archives & Records Administration, 1964.

National Archives. Letter from John Jay Knox to Abraham Lincoln, 1861. The Papers of Abraham Lincoln: Images from the National Archives and Library of Congress. (imagelink: https://s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/papersofabrahamlincoln/PAL_Images/PAL_PubMan/1861/02/238107.pdf)