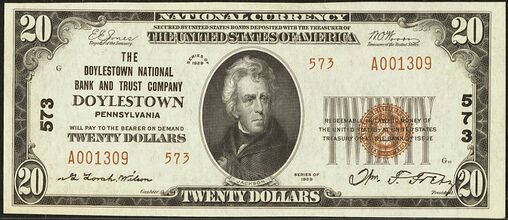

Doylestown National Bank/Doylestown NB & Trust, Doylestown, PA (Charter 573)

Doylestown National Bank/Doylestown NB & Trust Company, Doylestown, PA (Chartered 1864 - Closed 1970)

Town History

Doylestown is a borough in and the county seat of Bucks County, Pennsylvania. It is located 20 miles northwest of Trenton, 25 miles north of Center City Philadelphia, and 27 miles southeast of Allentown. It is part of the Delaware Valley, and the Philadelphia metropolitan area. As of the 2020 census, the borough population was 8,300. In 1860 the population was 1,432, reaching a 19th century high of 2,070 in 1880.

In March 1745, William Doyle, an Irish settler, obtained a license to build a tavern, then known as William Doyle's Tavern, on what is now the northwest corner of Dyers Road and Coryell's Ferry Road at present-day Main and State Streets. The tavern's strategic location at the junction of present-day U.S. Route 202, which links Norristown and New Hope, and Pennsylvania Route 611, which links Philadelphia and Easton, contributed to Doylestown's early growth. The Fountain House, at the corner of State and Main Streets, was built in 1758 and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

A second inn, named Sign of the Ship, was established in 1774, built diagonally across from the Doyle Tavern. Samuel Flack was innkeeper in 1778. On January 1, 1802, a post office was established in present-day Doylestown. Charles Stewart, the first postmaster, carried letters to recipients in the bell-shaped crown of his high beaver hat as he walked about the village. When Stewart died on February 7, 1804, his son-in-law Enoch Harvey became the next postmaster. In 1815, the first church was erected; it was followed by the construction of a succession of churches for various congregations throughout the 19th century.

As the population of Central and Upper Bucks County grew throughout the 18th and into the 19th century, discontent developed with the county seat's location in Newtown, where it had been since 1725. Eight petitions with a total of 184 signers were submitted to the General Assembly, some as early as 1784, requesting the move of the county seat to Doylestown. Among the signers were Andrew Armstrong, John Armstrong, John Davis, Andrew Denison, Jesse Fell, Joseph Fell, John Ingham (of Ingham Springs), Michael Frederick Kolb, Zebulon M. Pike (of Lumberton), Samuel Preston, Robert Shewell, Walter Shewell, and Fulkerd Sebring. The Pennsylvania General Assembly approved the move by an Act on February 28, 1810, and the first Court session was opened on May 11, 1813. An outgrowth of Doylestown's new courthouse was the development of "lawyers row", a collection of Federal-style offices. One positive consequence of early 19th-century investment in the new county seat was organized fire protection, which began in 1825 with the Doylestown Fire Engine Company.

A bill to erect Doylestown into a borough was introduced into Legislature in February 1830, but failed, as well as a second attempt in the session of 1832. "An Act to erect the Village of Doylestown, in the County of Bucks, into a Borough" was passed and signed into law by Governor Joseph Ritner on April 16, 1838.

An electric telegraph station was built in 1846, and the North Pennsylvania Railroad completed a branch to Doylestown in 1856. The first gas lights were introduced in 1854. Because of the town's relatively high elevation and a lack of strong water power, substantial industrial development never occurred and Doylestown evolved to have a professional and residential character.

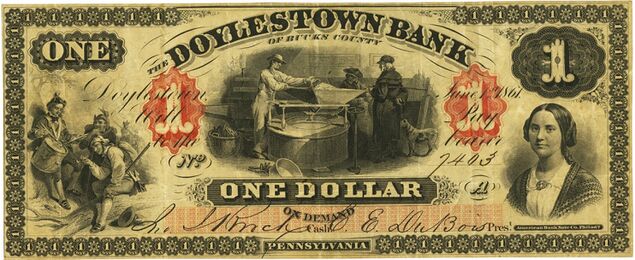

Doylestown had one National Bank chartered during the Bank Note Era, and it issued National Bank Notes. It also had one Obsolete Bank, The Doylestown Bank of Bucks County (Haxby PA-105), that issued Obsolete Bank Notes during the Obsolete Bank Note Era (1782-1866).

Bank History

- Organized November 2, 1864

- Chartered November 16, 1864

- Succeeded Doylestown Bank [Haxby PA-105]

- 1: Receivership July 30, 1903

- 1: Restored to solvency October 15, 1903

- 1: Merged with Central Trust Company of Doylestown with title change to The Doylestown National Bank and Trust Company in November 1926

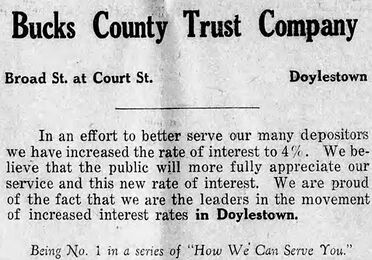

- 2: Merged with Bucks County Trust Company of Doylestown, February 1932

- Bank was Open past 1935

- For Bank History after 1935 see FDIC Bank History website]

- Closed April 20, 1970. Insured until Closed.

- Absorbed by PNC Bank, N.A., Wilmington, DE

Among the titles of Acts passed in the Legislative session of 1831-32 was No. 135, an Act to incorporate the Doylestown Bank of Bucks County.[1] The first regular meeting of the Doylestown Bank was held at the inn of David Wireman on November 26, 1832, when Abraham Chapman was elected president.[2] The following named gentlemen were elected directors: John Robbarts, Abraham Chapman, Benjamin Hough, Sr., E.T. McDowell, M.K. Taylor, Christian Clemmens, John Blackfan, John T. Neely, William Stokes, Timothy Smith, Samuel Kachline, Elias Ely, and Samuel Yardley.[3]

On Wednesday, November 16, 1864, the Doylestown National Bank with capital of $105,000 received authority to commence business. Charles E. DuBois was president and John J. Brock, cashier.[4]

On Sunday, June 16, 1872, Dr. Samuel C. Bradshaw of Quakertown died in that place in the 63rd year of his age. He was elected to Congress in 1854 by the Whig and American parties in the District composted of Bucks and Lehigh counties. He was a candidate for re-election in 1856, but was defeated by Judge Chapman. For the past 20 years he was connected with the Doylestown Bank mostly in the capacity of a director. He was a bachelor, although an important member of the social community.[5]

On Tuesday, January 19, 1875, stockholders of the Doylestown National Bank met and elected the following officers: George Lear, president; Mahlon K. Atkinson, A.D. Cernea, S.A. Firman, Benjamin G. Foulke, Daniel Gotwals, J.R. Haldeman, O.P. James, J.J. Reale, Joseph Rosenberger, and Wm. Thompson. After the election the stockholders and friends of the bank sat down to a sumptuous dinner at Corson's Hotel.[6] In December 1875, Hon. George Lear was appointed Attorney General of the State by Governor Hartranft. He was a native of Bucks County and a distinguished member of the recent Constitutional Convention. He studied law while attending a country store in Doylestown and was admitted to the bar in 1844. From 1846 to 1850 he served as Deputy Attorney General of Bucks County. Since March 1856, he had been president of the Doylestown National Bank, but continued to practice at the bar.[7]

In April 1876 the Doylestown National Bank had a new door made of iron, nearly a foot and a half square, placed on their vault. It was made by Ferring & Co., Philadelphia. The lock was made in such a manner as to be opened only at a certain time.[8]

In November 1879, at a meeting of the directors, John W. Gilbert of Buckingham was appointed a director of the bank to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Mahlon Atkinson, late of the same township.[9]

On Friday, May 23, 1884, ex-Attorney General George Lear died after an illness of several months.[10] He held the office of Attorney General until February 26, 1879, when he was succeeded by Henry W. Palmer. Henry Lear would succeed his father as president of the Doylestown National Bank.

On December 7, 1895, John J. Brock, for many years cashier of the Doylestown National Bank died at the age of 75. The Brock family came to the United States from England in 1762. He was the son of Stephen and Mary Brock and was born in Doylestown 75 years ago. His grandfather, John Brock who died in Philadelphia in 1844, was present at the battle of Trenton and stood guard there over the captured Hessians. He built the stone bridge over the Neshaminy at Bridge Point. Cashier Brock's first business venture was that of storekeeper in partnership with James B. Smith, son of General Samuel A. Smith in 1844. He sold out to Smith in 1846 and was appointed clerk in the Doylestown Bank. He was elected its cashier in 1857 and filled that position up to the time of his death. He left a widow and two children, George, an officer in the bank, and Mrs. Lear, wife of Henry C. Lear. He married Julia Philler, a daughter of George Philler and the sister of George Philler, president of the Philadelphia National Bank.[11]

In June 1897, the Doylestown National Bank announced it would occupy its new building.[12] This location at the crossing of Main and Court Streets was purchased at public sale and on it was erected a handsome and unique building, 50 by 82 feet; the height from the ground was 55 feet. The exterior walls were laid in red granite and Pompeian brick; the finish, inside and out, was of the most substantial character, while a massive vault contributed to the safety of the institution. The following directors composed the board which authorized the new building: Eugene James, Watson F. Paxson, J.B. Rosenberger, Dr. Harvey Kratz, Henry Lear, J. Simpson Large, John D. Walter, John L. DuBois and George Lear, president.[13]

In July 1900, Henry Lear of Doylestown was elected a member of the Executive Committee of the State Bar Association at its annual meeting at Cambridge Springs, Crawford County.[14]

In January 1901, about 400 well-known businessmen, together with members of the Bar, clergy and other professions, enjoyed the hospitality of the Doylestown National Bank dinner, a custom revived by the present cashier, George P. Brock, and initiated by his father, the late John J. Brock many years ago. The dinner was a pleasant event. Henry Lear was re-elected president of the bank and George P. Brock, cashier.[15]

According to the statement issued on February 25th, 1902, the aggregate of deposits subject to check amounted to $431,489.32, while the time certificates of deposit amounted to $582,837.96. The capital stock was $105,000, while the surplus fund was $110,000. The board of directors included Henry Lear, Watson F. Paxson, Rienzi Worthington, Francis L. Worthington, Dr. Harvey Kratz, Preston W. Hagerty, Burroughs Michener, J.B. Rosenberger, and John L. DuBois, Sr. The banking house, one of the most attractive and well-arranged of any in the State, was occupied in June 1897. The structure had every convenience for the transaction of the banking business and every effort was made to facilitate the wishes of the institution's patrons.[16] In March, a brazen attempt to steal "Saxon," a splendid Kentucky thoroughbred horse owned by George P. Brock was foiled by the caution of his keeper at Oliver Price's livery stables on Pine Street. A stranger attempted to get possession of the horse on a forged order.[17] In May, Cashier Brock was presented with a priceless Stradivarius violin by William Brock, a relative residing in Philadelphia.[18] In October, George P. Brock was in Sault Ste Marie to witness the opening of the 60,000 horse-power canal of the Consolidated Lake Superior Company.[19]

Wrecking of the Doylestown National Bank by Lear and Brock

In February 1903, in Doylestown borough the Republicans elected their candidate for burgess, George P. Brock, by a large majority and only lost one borough office.[20] His opponent was James Barrett, one of the town's free silver advocates.[21]

On Thursday, July 30, 1903, the following notice appeared on the door of the Doylestown National Bank: "This bank closed and in the hands of the Comptroller of the Currency." (signed) T.P. Cane, Deputy Comptroller of the Currency. W.S. Shofield, National Bank Examiner. The bank examiners had been working on the books for two days, but no statement was issued by them or the officers of the bank. The capital was $150,000 and the last report to the Comptroller showed surplus and profits $131,780; deposits over $1 million; loans and discounts and stock and securities $1,051,360, United States bonds to secure circulation $70,000; banking house furniture and fixtures $49,000; other real estate owned $14,293. According to Deputy Comptroller Kane, "The losses will absorb the entire surplus and capital stock of the bank. In other words, the total loss will amount to $215,000, and it devolves upon the directors and stockholders to make up the deficiency." Francis L. Worthington, a director, said: "The president and cashier ran things to suit themselves. They had no right to do so. They ought to have consulted the board of directors and this trouble would have been avoided. No one suspected anything wrong. Our stock has been increasing in value, advancing from $35 a share to $153. I suppose I will lose all through mismanagement of the officers. I understand there was some speculation, Consolidated Lake Superior, I believe, and in the stock most of the money may have been sunk." George P. Brock, cashier, declined to reply to the accusations of Mr. Worthington, saying: "Our investments did not turn out as well as we expected."[22] On September 17th, the stockholders of the defunct Doylestown National Bank met and decided to reorganize the institution. Henry Lear and George P. Brock tendered their resignations. The sub-committee's report on the affairs of the bank showed the good assets to amount to $806,587, doubtful $344,929, worthless $240,303. The doubtful and worthless assets it was suggested would under reorganization amount to $59,495 more than the valuation placed upon them by the receiver.[23]

The 1903 Consolidated Lake Superior riot occurred on 28–30 September 1903 in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada, as a result of layoffs and unpaid wages. Two police officers and four protesters were injured, company offices were looted, and elements of the Canadian army were called in to quell the unrest.

On Friday morning, January 8, 1904, former President Lear and Cashier Brock were taken into custody and arraigned before United States Commissioner Craig in Philadelphia where they waived a hearing and were held on bonds of $7,500 each for their appearance at the March term of court. The warrants were sworn out by Edward P. Moxey, national bank examiner, both approximately the same with $60,000 in Mr. Lear's case and in Mr. Brock's case, $70,000.[24] Later in January, the new cashier, Isaac P. Roberts resigned his position because the new board of directors was not disposed to holding the old board of directors responsible for the liability incurred in the bank's failure. Mr. Roberts did not wish to be considered as condoning any shielding of those responsible for losses and decided to make his protest more emphatic by resigning altogether. W. Henry Garges, one of the youngest clerks in the bank at the time of the failure was elected to succeed Mr. Roberts.[25]

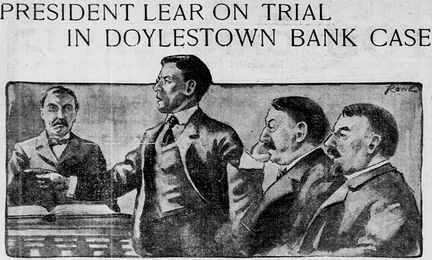

On September 28, 1904, Henry Lear, former president of the Doylestown National Bank was placed on trial before Judge McPherson in the United States District Couth in Philadelphia, charged with misappropriating funds of the bank. At the conclusion of the Lear case, George P. Brock, former cashier of the bank would be placed on trial charged with a like offense.[26] Henry Lear and George Philler Brock, sat beside their attorneys at a long table in the United States District Court facing charges of misappropriating the institution's funds, thereby causing its collapse. Linked by ties of kinship and associated all their lives in business, the two men were two-fold brothers-in-law, having married each other's sister. District Attorney Thompson opened the case against Henry Lear where 150 separate counts charged him with embezzlement, misapplication and abstraction of funds. Describing the method of the wrong-doing, the DA declared that the accused president would draw checks against the bank when he had no funds for their payment, and when the overdrafts reached a large amount he would give time or demand notes which would be placed to his credit on the books. Sometimes Lear's checks would be held in the cash without being charged to his account for months. Lear was aided by Cashier Brock in this way, allegedly conspiring together. Lawyer Graham strenuously objected to the DA's use of "conspiracy" as no such charge was made, and Judge McPherson limited the use of the term by the DA. Lear's total indebtedness amounted to $60,000 when the bank closed. William S. Hulshizer of Doylestown who had been connected with the bank since 1868 was the first witness for the Government. He was now bookkeeper in the bank. Hulshizer said the overdrafts allowed Lear were not all recorded during Brock's term as cashier, but that during part of the time former Cashier Worthington was connected with the bank. W.H. Garges, present cashier testified, producing three notes given by Lear to the bank with which the prosecution alleged he balanced his overdrawn accounts.[27]

Henry Lear's defense to the charge that he embezzled $60,000 from the Doylestown National Bank, by appropriating that amount of its funds to his own private use, was that he obtained the money honestly without any intent to cheat or defraud, but with the full knowledge and consent of the Board of Directors. The defendant, Henry Lear, was the principal witness in his own defense, while George Philler Brock, the accused cashier was the next in importance. Their testimony and that of the bank directors, when called in rebuttal, was the feature of the day's proceeding and constituted the vital part of the trial. When Mr. Lear took the stand he testified that he was admitted to the Bucks county bar in 1871. His father, George Lear, had been president of the Doylestown National Bank for twenty years prior to his death. In response to his attorney, Mr. Lear said he regretted that he would be compelled by the exigencies of the case to go into the indebtedness of his father which came to his knowledge upon the latter's demise. When he discovered how his father had been involved the witness said, he felt it his duty to assume the indebtedness which amounted to some $25,000 for the payment of the obligations. It was this desire to save the honor of his parent's credit that was the origin of his financial dealings with the bank. When he made his wishes and plans known to the Board of Directors, Mr. Lear continued, they suggested that he become president of the institution. Mr. Lear testified to the authority he said was vested in the cashier to allow overdrafts, and being a depositor in the bank, he declared he had as much right to borrow money as any other patron. "The bank never questioned that right." the witness reminded the jury with emphasis. "Did any one complain about the overdrafts?" queried counsel for the defense. "Mr. Large J. Simpson Large had been a director for 11 years and was once secretary of the board] testified yesterday he called me in relation to them, but I cannot recall any such conversation as he recited Were overdrafts permitted to be made by other customers? Certainly, it was a regular practice." Mr. Lear was then allowed to tell about the unpretentious mode of his living. He never had a horse and carriage, he said, and the one object of his life was to pay off his father's indebtedness. To this purpose applied all the proceeds of his early loans, which, after the obligations were wiped out, he renewed from time to time. Mr. Brock, former cashier of the bank, stated in answer to the questions put to him that he was elected cashier of the bank in 1900. He was preceded as cashier by L.P. Worthington. He knew the defendant, Henry Lear, who, in addition to being president of the bank, was a practicing lawyer. He explained that Lear's principal duty as president was preside over the meetings of the Board of Directors. "Was an overdraft of Mr. Lear's of $20,000 known to the Board Directors?" asked Mr. Graham. "Yes, sir." "Explain what was done in relation to that overdraft?" "It was converted into a note at the suggestion of the bank examiner, Mr. MacDugall. I told Mr. MacDugall, that Mr. Lear had no security to cover his note, but he said that made no difference. "Was this paper made by you in consequence of that suggestion of the bank examiner?" "Yes, sir." "Did you have authority between the board meetings to make discounts?" "Yes, sir." "And to allow overdrafts?" "Yes, sir, when I became cashier, I had a conversation with the members of the board in order that there might be a thorough understanding as to my duties and they left it entirely to my discretion to pass notes between meetings. They never turned down a note I said was good. I never was questioned as to my action at any time." "Did you have any understanding with Mr. Lear to let him have overdrafts without the knowledge of the board?" "None whatever. The overdrafts existed during the term of Mr. Worthington as cashier.”[28]

In December 1904, it was learned that Henry Lear would again be brought to trial by the Government. In the first trial the jury disagreed. Henry P. Brown of Philadelphia had been appointed a special assistant District Attorney to assist District Attorney Thompson in the retrial.[29]

The third trial of Henry Lear finished on Thursday, September 28, 1905. In the previous two trials, the last earlier in the year in February, the jury disagreed. The question of intent figured largely in the case and the evidence on both sides was voluminous. In the trial which began on Monday, September 25th, the prosecution, without going over much of the previous testimony sought to show that at the time Lear was getting large sums from the bank, he was being hard pressed by stock brokers for money to cover his margins. Evidence in the shape of letters from these brokers were produced and the bank directors were called to prove that they had no real knowledge of the extent of Lear's overdrafts, but signed statements to the Comptroller of the Currency as they were prepared by Cashier Brock without examining them. When the prosecution rested on Wednesday afternoon, George S. Graham, counsel for Lear startled the other side by announcing that the defense would not call any witnesses nor submit any testimony. Henry P. Brown, special assistant to DA Thompson said that he was totally unprepared to sum up and begged the court to adjourn. This was done.[30] After deliberating since noon Friday, the jury came into the Federal Court Saturday morning at 10:45 o'clock and asked Judge McPherson for instructions on the second count in the bill of indictment. Upon receiving the instruction, they conferred for a few moments and then said they were ready to give their verdict. The foreman then handed in a verdict of guilty on the third count which charged the misapplication of the funds in the bank. The penalty for this was not less than five years and not more than ten years in the penitentiary. Mr. Petit immediately moved for a new trial and Judge McPherson allowed them a few days to present their reasons and increased Mr. Lear's bail from $7,500 to $10,000, giving hm a week to secure the bondsmen.[31] Judge McPherson on Friday, December 29th refused to grant a new trial. Although the federal authorities had the power under the decree to immediately arrest Lear, this was not thought necessary as his $10,000 bail was thought sufficient to hold him pending the final disposition of the case. Lear's counsel planned an to take the case to the United States circuit court of appeals.[32]

On Thursday, October 25, 1906, the United States Appellate Court handed down the mandate in the case of Henry Lear who was recently refused a new trial by Judge Gray. The document called for the execution of the five years' sentence imposed by the lower court. Lear would have five days' grace before surrendering himself to Government officials.[33] Accompanied by his two sons and George P. Brock who was also convicted for the concern's wrecking, Lear appeared at the United States District Attorney's office shortly after noon on the 30th and was driven in a carriage which the deputy marshal had waiting on Ninth Street to Cherry Hill where the heavy doors quickly closed on the convicted financier.[34]

On Tuesday, December 18, 1906, George Philler Brock, convicted cashier of the Doylestown National Bank began his five-year sentence in the Eastern Penitentiary. He went to Philadelphia accompanied by his wife and a friend and was quietly taken to the 'Pen' in a cab. Without any show of feeling, he left them and entered the prison where, six hours after he had taken dinner at the St. James Hotel, he supped with the other convicts. It was reported that his friends would lose no time in endeavoring to secure a pardon for him and Henry Lear, former president of the bank.[35]

Restored to Solvency by Dr. John N. Jacobs

The Doylestown National Bank, which was closed by order of the Comptroller of the Currency on July 30, 1903, reopened for business on Thursday morning, October 15th. Dr. J.N. Jacobs of Lansdale, the new President, said there would be enough money on hand to pay every depositor and creditor to the last dollar, if they wanted their money. At a meeting last Saturday, the new board of directors was sworn in, and Receiver Lyons was notified that the $220,000 required by the Comptroller was ready. Then came a few preliminaries--the Receiver telegraphed the facts to Washington, the Comptroller sent on a special representative in the person of Judge F.F. Oldham who in turn telegraphed that the bank officials had complied with every requirement, and Tuesday evening the Comptroller telegraphed back his consent and ordered the bank's assets turned over to the new management. Then, the directors announced that the bank would reopen Thursday morning with enough cash on hand to meet every obligation on demand. The new board of directors as reorganized on Saturday was as follows: Dr. John N. Jacobs of Lansdale, president; Burroughs Michener, Mechanicsville; Preston W. Hagerty, Chalfont; John F. Shaddinger, Gardenville; John G. King, Fountainville; Edward R. Kirk, Pineville; Edward D. Worstall, Jamison; William D. Rowland, Dublin; and William Neis, Doylestown. Isaac R. Roberts, formerly of the Tradesmen National Bank, Conshohocken, was elected cashier.[36]

In January 1911, John M. Jacobs, formerly of Lansdale, was elected president of the Doylestown National Bank, his father, Dr. J.N. Jacobs taking the position of vice president. The younger Jacobs had 24 years' experience in the banking business, having been treasurer of the Montgomery Trust Company of Norristown for 8 years and secretary and treasurer of the Lansdale Trust Company for ten years. Previous to that he was a clerk in the Perkiomen National Bank.[37]

In February 1915, Dr. John N. Jacobs, reorganizer of the Doylestown National Bank announced that it had been decided at the directors' meeting to organize a new trust company which would use the national bank's banking house as its headquarters. It would be known as the Central Trust Company with capital stock $250,000.[38] In September the directors of the Central Trust Company of Doylestown organized by electing officers. Officers and directors were as follows: John N. Jacobs, president; John M. Jacobs, treasurer; Edward R. Kirk, secretary; John M. Jacobs, Theodore M. Moyer, Preston W. Hagerty, Edward R. Kirk, John N. Jacobs, Edward W. Utz, William F. Fretz, Burroughs Michener, Dr. William S. Erdman, Charles M. Meredith, Albert W. Preston, Edward B. Search, William D. Rowland, Frank L. Worthington, John A. Gross, Wilson S. Bergey, Phineas J. Walker, and George E. Closson, directors.[39]

In January 1926, at the annual meeting of the Bucks County Trust Company, the oldest in the county, it was directed that plans be made for the erection of a handsome new banking building in the heart of the borough on two sites recently purchased. The following officers were elected: Henry A. James, president; Oscar O. Bean, first vice president; Claude S. Wetherill, second vice president; George H. Miller, secretary and treasurer; and Harry Garner, assistant secretary.[41]

In October 1926, announcement of the merger of the Central Trust Company of Doylestown and the Doylestown National Bank was made by John N. Jacobs, president of the bank and Edward R. Kirk, president of the trust company. The former was a son of the late Dr. John N. Jacobs, Lansdale borough official who was also identified with Doylestown financial circles. The stockholders of the Central Trust Co. would be asked to ratify a resolution to sell the business to the Doylestown National and to liquidated and dissolve the Central Trust Co. Stockholders of the Doylestown National would be asked to pass upon four resolutions. One called for an increase of $35,000 in the capital stock, making a total of $140,000. The second to give authority to open a trust department, the third provided for a change in the name of the institution to "The Doylestown National Bank and Trust Company," and the fourth arranged for the purchase of the assets and business of the trust company. If approved by the stockholders, Doylestown would have but one banking institution.[42]

On Saturday, February 13, 1932, Oscar O. Bean, president of the Bucks County Trust Company and William F. Fretz, president of the Doylestown National Bank announced the consolidation of the two institutions culminating a year of negotiations. President Oscar O. Bean and former Senator Joseph R. Grundy of Bristol, director of the Bucks County Trust Co., would both be members of the board of directors of the national bank. Resources of the banks totaled over $3,600,000 with trust funds well over $3,200,000.[43] On Tuesday, May 17, 1932, The Doylestown National Bank and Trust Company purchased the building occupied by the Bucks County Trust Company prior to the consolidation of the two institutions and would move at once into the new quarters. It became known at the same time that the building formerly occupied by the Doylestown National Bank had been sold to Bucks County and would be occupied by the county commissioners and the county treasurer as well as one or two other officers not yet determined. The move was made to relieve congestion in the courthouse where several important interior changes were planned. The Bucks County Trust building was entirely modern, was erected specifically for bank occupancy and would prove an asset to the consolidated bank. It was owned by the stockholders of the Bucks County Trust Company, not having been included in the transfer of the assets when that institution was taken over by the national bank. The bank planned to open for business in its new quarters on Monday, May 23rd.[44] Up-to-date vaults, a ground-floor entrance, modernly-arranged banking equipment for handling in the most efficient manner the affairs of the bank were but a few of the advantages of the new home of the Doylestown National Bank and Trust Company. The directors included the following: William F. Fretz, Pipersville, president; Howard M. Barnes, Doylestown, vice president and trust officer; Edward R. Kirk, Pineville, second vice president; Burroughs Michener, Doylestown, third vice president; Albert W. Preston, Solebury, secretary; John M. Jacobs, Lansdale; J. Carroll Molloy, Pineville; Theodore M. Moyer, Ferndale, Preston W. Haggerty, Chalfont; Edward W. Utz, Wismer; Joseph F. Worstall, Doylestown; Leidy S. Gruver, Dublin; William Tinsman, Lumberville; Edward B. Search, Churchville; Joseph R. Grundy, Bristol; and Oscar O. Bean, Doylestown. The following year the bank would be able to celebrate its 100th anniversary in an appropriate building.[45]

Application for a charter for the Bucks County Trust Company of Doylestown was made on January 23, 1886.[46] The State Department issued a charter in February with the capital set at $250,000.[47] Lots were purchased directly opposite the Court House on Broad Street for the erection of a handsome building.[48] Incorporated on February 23, 1886, Judge Richard Watson was elected president. Succeeding presidents were Hon. George Ross, Hugh B. Eastburn, George Watson, Henry A. James,[49] and Oscar O. Bean. [The Bucks County Trust Co. was located in a red brick bank structure built in 1887 at East Court and Broad Streets, later occupied by the Melinda Cox Free Library][50]

On Monday evening, March 25, 1935, John M. Jacobs, prominent retired banker, died at his home at Fifth and Broad Streets, Lansdale, a short time after suffering a heart attack. He was 68 years old. The banker was associated with his father, the late Dr. John N. Jacobs, one-time president of Lansdale Borough Council, in many banking ventures, frequently taking weakening institutions and placing them on firmer financial footing. Mr. Jacobs, first entered into this father-and-son arrangement at East Greenville where he took his first banking job. Later he was associated with his father in the organization of the old Lansdale Trust Company, which had its offices in the Music Hall block about thirty-five years ago. After the institution passed out of the Jacobs' hands it became the former Citizens National Bank. From Lansdale Mr. Jacobs went to the Montgomery Trust Company at Norristown where he was cashier, and about 1905, he became associated with his father at Doylestown where they reorganized the Doylestown National Bank. The younger Jacobs ultimately became president of the institution, which position he held until about three years ago, when he retired from active association with banking institutions. He moved to Lansdale, and set up a bond and investment business which he continued to the time of his death. His Lansdale home was just a square away from that of his father who died eleven years ago at Fourth and Broad.[51]

In January 1939, at an organization meeting held by the Doylestown National Bank and Trust Company, William F. Fretz, Pipersville, was elected president. Other officers included Edward R. Kirk, Wycombe, first vice president; Burroughs Michener, Doylestown, second vice president; Albert W. Preston, Solebury, vice president and secretary; Howard M. Barnes, executive vice president and trust officer; G. Lorah Wilson, cashier; George E. Moyer, assistant trust officer; J. Carroll Molloy and S. Calvin Roberts, assistant secretaries. The 15 directors included William F. Fretz, Edward R. Kirk, Burroughs Michener, Theodore Moore, Joseph R. Grundy, Oscar O. Bean, Amos Kirk, A. Walter Fretz, Simon K. Moyer, Edward Search, J. Carroll Molloy, Joseph F. Worstall, William Tinsman, A.W. Preston, and Howard M. Barnes.[52]

On January 17, 1952, A. Walter Fretz, well-known Bucks County trousers manufacturer, was re-elected president of the Doylestown National Bank & Trust Company. He was the youngest bank president in the county. Edward R. Kirk of Wycombe was elected vice president and chairman of the board. The executive vice president and trust office was Howard M. Barnes, Doylestown.[53]

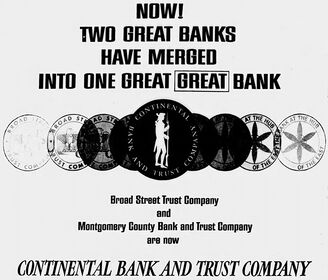

In August 1965, the Broad Street Trust Company and Montgomery County Bank and Trust Company merged to form the Continental Bank and Trust Company with 36 offices in Philadelphia, Montgomery, Delaware and Chester Counties.[54]

In December 1969, shareholders of the Continental Bank of Norristown and the Doylestown National Bank and Trust Company voted their approval of the merger plan. Continental maintained 42 offices throughout the area. Roy T. Peraino, president and chief executive officer of Continental Bank announced net income for the year ending 1969 reached a record high of $7,250,000 or $3.20 per share, representing a 26% increase earned in 1968. Total resources at year end reached $609,170,000 and deposits totaled $501,378,000.[55] The consummation of the merger would give Continental its first representation in the Bucks County area with six additional offices in Buckingham, Doylestown, the Doylestown Shopping Center, Plumsteadville, Warminster, and Warrington.[56][57] The Doylestown National Bank's building situated at the point of Courthouse Park between East Court and North Main Streets was an imposing yellow brick structure, purchased by the Bucks County Commissioners as a Courthouse annex. During the 30s when a rumor swept the underworld in Philadelphia that the bank would be held up, State Policemen kept watch out of the windows in the newspaper building armed with high-powered weapons. The rumor started by a woman in a bar turned out to be a fluke.[58] The Doylestown National became Continental Bank on Monday, April 20th. With the merger of Doylestown Trust Company with Industrial Valley Bank and Doylestown National Bank & Trust Company with Continental, only Doylestown Federal Savings & Loan retained Doylestown in its name.[59]

- 01/01/1921 Institution established. Original name: Continental Bank (FDIC# 475).

- 04/20/1970 Participated In Absorption/Consolidation/Merger with The Doylestown National Bank and Trust Company (Charter 573)

- 09/29/1980 Acquired The Solebury National Bank of New Hope (Charter 11015) (FDIC# 7654) in New Hope, PA.

- 06/25/1982 Acquired Lincoln Bank (FDIC# 19241) in Bala Cynwyd, PA.

- 08/27/1994 Merged and became part of Midlantic National Bank (FDIC# 6384) in Newark, NJ.

- 09/06/1996 Changed Institution Name to PNC Bank, National Association.

Official Bank Titles

1: The Doylestown National Bank, Doylestown, PA

2: The Doylestown National Bank and Trust Company, Doylestown, PA (11/9/1926)

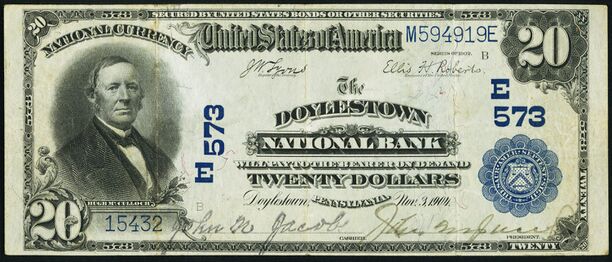

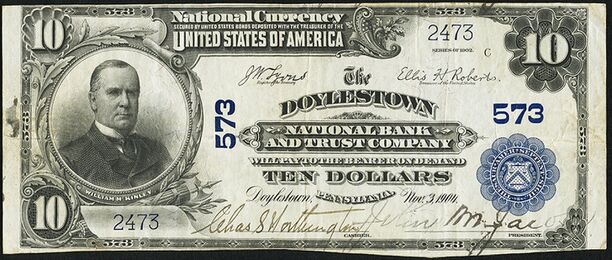

Bank Note Types Issued

A total of $2,533,850 in National Bank Notes was issued by this bank between 1864 and 1935. This consisted of a total of 232,911 notes (202,904 large size and 30,007 small size notes).

This bank issued the following Types and Denominations of bank notes:

Series/Type Sheet/Denoms Serial#s Sheet Comments 1: Original Series 4x5 1 - 3250 1: Original Series 3x10-20 1 - 2400 1: Series 1875 4x5 1 - 2495 1: Series 1875 3x10-20 1 - 1904 1: 1882 Brown Back 4x5 1 - 6307 1: 1882 Brown Back 3x10-20 1 - 3820 1: 1902 Red Seal 3x10-20 1 - 4100 1: 1902 Date Back 3x10-20 1 - 8900 1: 1902 Plain Back 3x10-20 8901 - 22431 2: 1902 Plain Back 3x10-20 1 - 4019 2: 1929 Type 1 6x10 1 - 3328 2: 1929 Type 1 6x20 1 - 748 2: 1929 Type 2 10 1 - 4135 2: 1929 Type 2 20 1 - 1416

Bank Presidents and Cashiers

Bank Presidents and Cashiers during the National Bank Note Era (1864 - 1935):

Presidents:

- Charles E. Dubois, 1864-1866

- George Lear, 1867-1883

- Henry Lear, 1884-1902

- Dr. John N. Jacobs, 1904-1910

- John Miller Jacobs, 1911-1928

- William F. Fretz, 1929-1935

Cashiers:

- John Jones Brock, 1864-1895

- Lewis Palmer Worthington, 1896-1899

- George P. Brock, 1900-1902

- Isaac B. Roberts, 1903-1904

- William Henry Garges, 1904-1906

- John G. King, 1907-1910

- Dr. John N. Jacobs, 1911-1923

- Edward Roberts Kirk, 1924-1926

- Charles Smith Worthington, 1927-1928

- George Lorah Wilson, 1929-1935

Other Known Bank Note Signers

- No other known bank note signers for this bank

Bank Note History Links

- Doylestown National Bank, Doylestown, PA History (NB Lookup)

- Pennsylvania Bank Note History (BNH Wiki)

- Warden, Jr., William B., "The Doylestown Bank," Paper Money, Whole No. 32, 1969, pp 113-4.

- Wait, George, "Doylestown Bank (addenda)," Paper Money, Whole No. 34, 1970, pp 72-3.

Sources

- Doylestown, PA, on Wikipedia

- Don C. Kelly, National Bank Notes, A Guide with Prices. 6th Edition (Oxford, OH: The Paper Money Institute, 2008).

- Dean Oakes and John Hickman, Standard Catalog of National Bank Notes. 2nd Edition (Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 1990).

- Banks & Bankers Historical Database (1782-1935), https://spmc.org/bank-note-history-project

- ↑ The Patriot, Harrisburg, PA, Tue., Apr. 10, 1832.

- ↑ The Bucks County Gazette, Bristol, PA, Thu., Mar. 27, 1902.

- ↑ The United States Gazette, Philadelphia, PA, Wed., Nov. 28, 1832.

- ↑ National Republican, Washington, DC, Fri., Nov. 18, 1864.

- ↑ Lansdale Reporter, Lansdale, PA, Thu., June 20, 1872.

- ↑ Lansdale Reporter, Lansdale, PA, Thu., Jan. 28, 1875.

- ↑ Daily Local News, West Chester, PA, Tue., Dec. 7, 1875.

- ↑ The Bucks County Gazette, Bristol, PA, Thu., Apr. 27, 1876.

- ↑ The Bucks County Gazette, Bristol, PA, Thu., Nov. 27, 1879.

- ↑ New-York Tribune, New York, NY, Sat., May 24, 1884.

- ↑ The Philadelphia Times, Philadelphia, PA, Sun., Dec. 8, 1895.

- ↑ The Bucks County Gazette, Bristol, PA, Thu., June 17, 1897.

- ↑ Paper Money, Whole No. 32, 1969, pp 113-4.

- ↑ The Bucks County Gazette, Bristol, PA, Thu., July 5, 1900.

- ↑ The Bucks County Gazette, Bristol, PA, Thu., Jan. 17, 1901.

- ↑ The Bucks County Gazette, Bristol, PA, Thu., Mar. 27, 1902.

- ↑ Lansdale Reporter, Lansdale, PA, Thu. Mar. 20, 1902.

- ↑ News Herald, Perkasie, PA, Thu., May 15, 1902.

- ↑ News Herald, Perkasie, PA, Thu., Oct. 30, 1902.

- ↑ The Allentown Leader, Allentown, PA, Mon. Feb. 23, 1903.

- ↑ The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, PA, Sun., Feb. 1, 1903.

- ↑ Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, Wilkes-Barre, PA, Thu., July 30, 1903.

- ↑ The Semi-Weekly Gazette and York Democratic Press, York, PA, Sat., Sep. 19, 1903.

- ↑ The Bucks County Gazette, Bristol, PA, Thu., Jan. 14, 1904.

- ↑ Courier-Post, Camden, NJ, Thu., Jan. 14, 1904.

- ↑ Lancaster Examiner and The Semi-Weekly New Era, Lancaster, PA, Sat., Oct. 1 1904.

- ↑ The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, PA, Thu., Sep. 29, 1904.

- ↑ The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, PA, Sat., Oct. 1, 1904.

- ↑ News Herald, Perkasie, PA, Thu., Dec. 1, 1904.

- ↑ The Daily Republican, Phoenixville, PA, Thu., Sep 28, 1905.

- ↑ The Record, West Chester, PA, Thu., Oct. 5, 1905.

- ↑ Lancaster Daily Intelligencer, Lancaster, PA, Sat., Dec. 30, 1905.

- ↑ The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, PA, Fri., Oct. 26, 1906.

- ↑ The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, PA, Tue., Oct. 30, 1906.

- ↑ The Bucks County Gazette, Bristol, PA, Fri., Dec. 21, 1906.

- ↑ The Reporter, Lansdale, PA, Thu., Oct. 15, 1903.

- ↑ The Reporter, Lansdale, PA, Tue. Jan. 21, 1936.

- ↑ The Bristol Daily Courier, Bristol, PA, Thu., Feb. 4, 1915.

- ↑ News Herald, Perkasie, PA, Wed., Sep. 29, 1915.

- ↑ North Penn Reporter, Lansdale, PA, Mon., Jan. 23, 1928.

- ↑ North Penn Review, Lansdale, PA, Wed., Jan. 13, 1926.

- ↑ North Penn Review, Lansdale, PA, Wed., Oct. 20, 1926.

- ↑ The Bristol Daily Courier, Bristol, PA, Mon., Feb. 15, 1932.

- ↑ North Penn Reporter, Lansdale, PA, Wed., May 18, 1932.

- ↑ The Bristol Daily Courier, Bristol, PA, Wed., May 18, 1932.

- ↑ The Central News, Perkasie, PA, Thu., Jan. 28, 1886.

- ↑ Harrisburg Telegraph, Harrisburg, PA, Tue., Feb. 2, 1886.

- ↑ The Reporter, Lansdale, PA, Thu., Feb. 4, 1886.

- ↑ The Central News, Perkasie, PA, Wed., Jan. 8, 1930.

- ↑ The Daily Intelligencer, Doylestown, PA, Thu., Mar. 5, 1970.

- ↑ North Penn Reporter, Lansdale, PA, Tue., Mar. 26, 1935.

- ↑ The Bristol Daily Courier, Bristol, PA, Sat., Jan 21, 1939.

- ↑ The Bristol Daily Courier, Bristol, PA, Fri., Jan. 18, 1952.

- ↑ The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, PA, Mon., Aug. 2, 1965.

- ↑ The Mercury, Pottstown, PA, Tue., Jan. 20, 1970.

- ↑ Delaware County Daily Times, Chester, PA, Fri., Feb. 27, 1970.

- ↑ The Daily Intelligencer, Doylestown, PA, Thu., Mar. 5, 1970.

- ↑ The Daily Intelligencer, Doylestown, PA, Tue., Mar. 3, 1970.

- ↑ The Daily Intelligencer, Doylestown, PA, Fri., Apr. 3, 1970.